In skilled nursing facilities (SNFs), staff members often find the Patient-Driven Payment Model (PDPM) process complex and unfamiliar, especially when determining how Medicare (and, in many states, Medicaid) payment is calculated. PDPM is based on five separate case-mix adjusted components: Physical Therapy (PT), Occupational Therapy (OT), Speech Language Pathology (SLP), Nursing, and Non-Therapy Ancillary (NTA), along with a non-case-mix component. Each one is identified using specific resident characteristics captured on the Minimum Data Set (MDS) assessment, such as diagnosis, surgical history, functional status, and clinical conditions. (Note: Not all states pay based on all five components, but each MDS calculates all five.)

This article, part 1 of a five-part PDPM series, focuses on the PT and OT components that have separate payment rates but are calculated the same way. Accurate primary diagnosis and section GG scoring are key to supporting the PT and OT components. Staff need to understand how this calculation works and be aware of common mistakes that can affect reimbursement.

Primary Diagnosis and Clinical Category

Calculating the PT and OT components begins by identifying the resident’s primary diagnosis, the condition that best describes the primary reason for the Medicare Part A stay (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services [CMS], 2024a). Importantly, the diagnosis selected does not need to match the hospital’s discharge diagnosis. Rather it must represent the primary reason the resident is receiving skilled services in the facility. It should be an interdisciplinary team (IDT) decision supported by the medical record documentation. For Medicaid use, this reflects the main reason for the long-term care stay. Physician assignment, therapy and nursing input, and IDT clinical judgment must all align to support the selection of the primary diagnosis. For more information, see the AAPACN article “I0020B: Avoid Common Sources of Confusion When Coding This MDS Item.”

Equally important is adherence to ICD-10-CM coding rules. Certain codes, such as manifestation codes, cannot be used as the primary diagnosis. For example, if the main reason for the stay is dementia, but it is documented as a manifestation of Alzheimer’s disease, then Alzheimer’s disease must be coded as the primary diagnosis, with dementia as secondary. Similarly, codes with “code first” or “in diseases classified elsewhere” designations in the ICD-10-CM coding guidelines must be handled appropriately, ensuring the underlying condition is selected as the primary (CMS, 2024b). For more information on proper ICD-10-CM coding sequencing, see the AAPACN article “Deep Dive into ICD-10-CM: Diagnosis Sequencing Guidelines.”

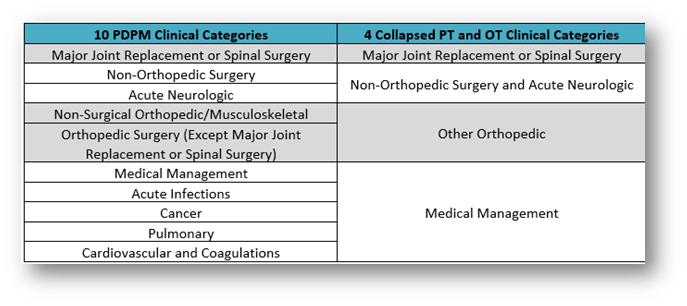

The primary diagnosis code is entered on MDS item I0020B and places the resident into one of PDPM’s default clinical categories. This category reflects the primary clinical reason for the potential need for rehabilitation services. Figure 1 shows how the 10 clinical categories collapse into 4 major clinical categories.

Figure 1

A PT/OT clinical category will be assigned regardless of actual therapy minutes delivered. In some cases, the default clinical category will be modified if the resident underwent specific types of major surgeries, identified in section J of the MDS, during the qualifying hospital stay.

The Impact of Section J on Clinical Category

Items J2300 to J5000 of the MDS capture any major surgical procedures performed during the resident’s prior inpatient hospitalization. These procedures are documented using checkboxes rather than diagnosis codes. They are not subject to ICD-10-CM coding rules as seen in section I of the MDS. Coding a qualifying surgery in this section may modify the resident’s clinical category and lead to a higher PT and OT payment classification. This applies in particular for procedures such as major joint replacements, spinal surgeries, and other orthopedic interventions.

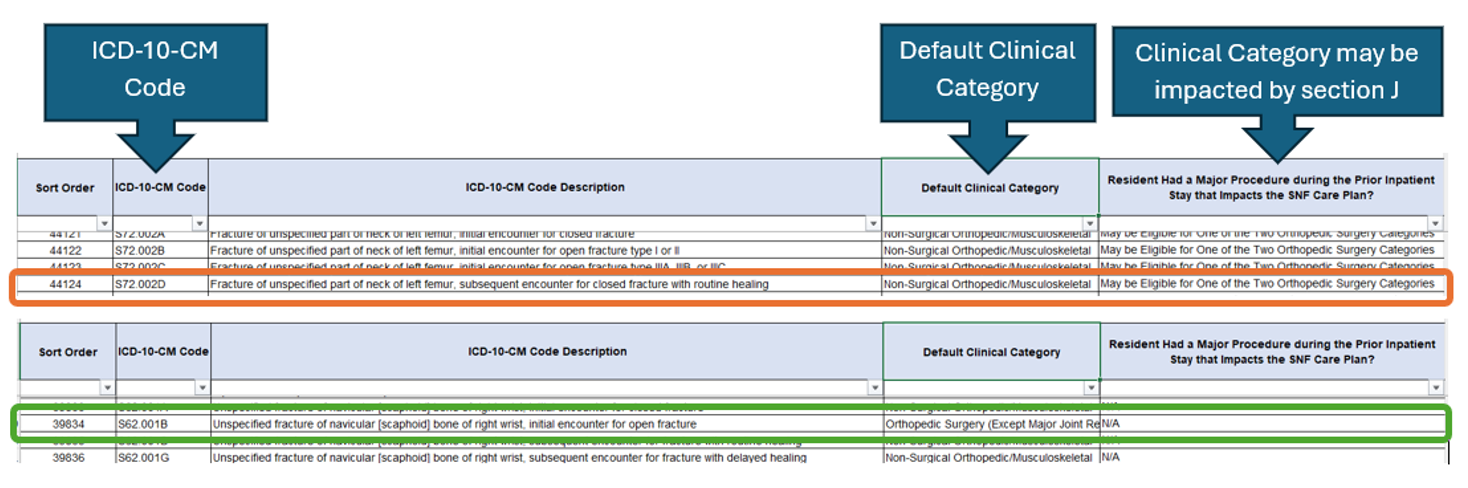

However, not all surgeries have an impact on the default clinical category, and the PDPM mapping file will indicate when a surgical category adjustment is applicable. Although the mapping file is built into the PDPM grouper in the MDS software, it is good to be familiar with which ICD-10-CM codes are impacted by section J. The PDPM mapping file can be found here under PDPM resources for each fiscal year. In Figure 2, the orange box shows an ICD-10-CM code impacted by section J (May be Eligible for One of the Two Orthopedic Surgery Categories). The green box shows an ICD-10-CM code that is not impacted by section J (N/A).

Figure 2

After determining the final clinical category, the resident’s function score is calculated, derived from section GG of the MDS. This portion of the assessment focuses on the resident’s usual performance in key self-care and mobility areas. Items such as eating, oral hygiene, toileting hygiene, transfers, and ambulation are evaluated and coded on the MDS. For the 5-Day Prospective Payment System (PPS) assessment, data is collected during the first three days of the Medicare stay. For an Interim Payment Assessment (IPA), the observation window includes the assessment reference date (ARD) and the two prior calendar days. For more information on section GG observation periods, see the AAPACN tool Section GG 3-Day Assessment Periods and Algorithm.

A common point of confusion among new section GG users is the concept of “usual performance.” It refers not to the resident’s best or worst performance during the observation period, but rather how he or she generally performs most of the time during that period. Observations should be made across multiple situations and involve input from a variety of care staff. An interdisciplinary approach is essential. Nursing staff, therapy, certified nursing assistants (CNAs), and even the resident and their family can all offer valuable insights that lead to a more accurate reflection of the resident’s functional status. AAPACN provides a large variety of training and information on section GG completion (see list of additional resources at the end of this article).

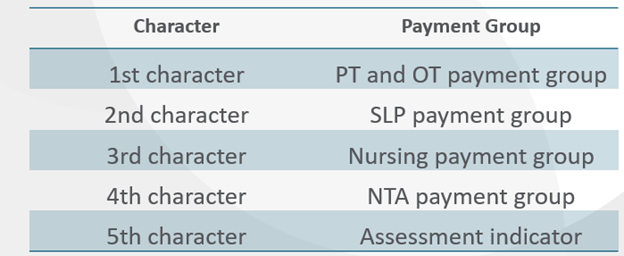

Once the function score is calculated and combined with the clinical category, the system generates a payment code. It is listed on the claim called a Health Insurance Prospective Payment System (HIPPS) code that assigns the resident to a specific case-mix group for the PT and OT components and reflects the first character of the HIPPS code. The full HIPPS code corresponds to each case-mix group assigned to the other case-mix adjusted PDPM components, as well as an assessment indicator to identify the corresponding assessment type (Figure 3).

Figure 3

Potential PT/OT Component Missteps

Primary Diagnosis

Many new PDPM users encounter obstacles during the MDS process. One of the most frequent missteps is selecting a primary diagnosis based on payment potential rather than the primary reason for services. For example, a facility may be tempted to code aphasia to trigger higher reimbursement through the SLP component, even though most of the skilled services being delivered are related to a recent hip fracture. In such cases, the fracture should be coded as the primary diagnosis to reflect the true reason for therapy and nursing involvement, regardless of the impact of the diagnosis on final payment. Medical record documentation must support the primary diagnosis determination.

Another common mistake involves the improper use of “Z” aftercare ICD-10-CM codes when a resident has a fracture as a primary diagnosis. ICD-10-CM coding guidance clearly indicates that no aftercare codes should be used for injuries or fractures. The subsequent encounter 7th character code must be used instead (CMS, 2024b). This subsequent encounter (often seen as “D” to reflect a subsequent encounter with routine healing) is intended to reflect all the aftercare provided for the injury or fracture, including any surgical aftercare.

For instance, if a resident had a hip fracture treated with a joint replacement, the primary diagnosis must reflect the fracture ICD-10-CM code, not the aftercare of a joint replacement code. When the hip replacement is coded properly at J2310 on the MDS, the resident will then qualify for the Major Joint Replacement surgical clinical category, resulting in a more appropriate payment rate.

Section GG

Inaccurate coding of section GG is another common and costly mistake in the PT and OT components of PDPM. Because the function score directly affects payment, overstating or understating a resident’s usual performance can lead to underpayment, overpayment, or compliance issues. Errors often occur due to poor staff understanding, limited observation and documentation, or lack of interdisciplinary input.

Relying on one staff member to complete the usual performance determination for section GG is another pitfall. CMS anticipates that the IDT of qualified clinicians has evaluated the resident during the assessment period (CMS, 2024a). Facilities must educate staff on the different self-care and mobility tasks and performance levels. “Usual performance” determination should involve therapy and nursing input, along with documentation to support this collaboration. Staff should perform routine audits to confirm that documentation supports MDS coding. Accurate coding not only ensures proper reimbursement but also reflects the resident’s true functional status for care planning and quality outcomes.

Conclusion

The PT and OT components of PDPM follow a structured multistep process that begins with clinical accuracy and ends with data-driven classification. From correctly selecting and coding the primary diagnosis, to identifying surgical procedures, to capturing functional performance in section GG, each step requires precision, teamwork, and a strong understanding of PDPM methodology. For new users, mastering this process is essential not only for supporting accurate reimbursement, but also for ensuring residents receive the care they need, based on a true representation of their condition and abilities.

By following best practices and avoiding common pitfalls, SNF teams can confidently navigate the complexities of PDPM and be assured that their assessments are both compliant and clinically sound.

Additional AAPACN ICD-10-CM Resources

- Five Mistakes Often Made Selecting ICD-10-CM Codes in the SNF (Article)

- How to Use the ICD-10-CM Coding Manual (Article)

- ICD-10-CM: Navigating the Term “With,” Combination Codes, and Complications of Care (Article)

- Deep Dive into ICD-10-CM Coding: Misunderstood Coding Guidelines (Article)

- ICD-10 Coding: Keys to Achieving the Highest Specificity (Article)

- ICD-10-CM Coding Certificate Program for SNFs (Certificate program)

- RAC-CT – Introduction to ICD-10-CM Coding for Long-Term Care (Education course)

Additional AAPACN Section GG Resources

- Section GG: Key Insights into Determining Usual Performance (Podcast)

- Section GG Strategies: Documentation and Collaboration (Article)

- Solving the Mystery: How to Document for Section GG (Article)

- Section GG Process Flow Chart (Tool)

- GG Trivia Game (Tool)

- GG Driver’s Manual (For-sale product)

- Section GG Train-the-Trainer (Certificate program)

Additional AAPACN PDPM Resources

- PDPM Overview for Supporting SNF Staff (Article)

- Accurate PDPM Reimbursement: Four Areas of Focus to Shore Up MDS Documentation (Article)

- Common PDPM and MDS Coding Missteps (Podcast)

- PDPM At-a Glance (Tool)

- PDPM Game Plan (For-sale product)

References

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. (2024a). Long-term care facility resident assessment instrument 3.0 user’s manual (version 1.19.1). https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/NursingHomeQualityInits/MDS30RAIManual.html

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. (2024b). ICD-10-CM official guidelines for coding and reporting, FY 2024 (October 1, 2024 – September 30, 2025). https://www.cms.gov/files/document/fy-2025-icd-10-cm-coding-guidelines.pdf